ABRIDGED Excerpt from Chapter One

DESIRE, HEARTBREAK

In February 2014, after being single for years, I began seeing a man who was divorced, nearing forty, and feeling his own clock ticking. When I read online that the chances of everyone’s first marriage working out aren’t great but that divorced men tend to stick with their second wives until the end, I got over the fact of his divorce pretty fast. He had moved to Salt Lake City for a job, he told me, and it paid well enough to support a family.

A few months later, I would turn him into the Portuguese lover, but the Portuguese lover is a fiction. Everything about the Portuguese lover is a fiction.

Everything is a story. You are a story—I am a story.[1]

—

After I learned that he always carried a Sharpie so that he could draw a dick and balls on something in every public building he went into, I opted out and never saw him again.

Some time later, I was invited to dinner by the man I would end up dating for the next sixteen months. This man would become the young lover.

Not everything about the young lover is a fiction—least of all the way her body existed only where he touched her.[2]

—

Who said this? That the only way to know when you’re done with a book is to have two projects going simultaneously. Then one day when you realize you’ve been putting all your energy into the newer project, that’s when you’ll know you’re done with the old one.

I was getting closer to finishing Desire, and so I put away that draft to see if it could survive time and distance, and I began preparing a new book.

I already had the title: Fit Into Me.

—

As I had done for my first two books, I began to develop a word bank. This time from Anne Carson’s translation of Sappho, If Not, Winter.

I transcribed all the nouns and verbs, printed them, cut them up like refrigerator poetry magnets, put them in a giant Ziploc bag, and shook, sifted, swirled, mixing and separating as best I could. Then I pulled them out one at a time to transcribe lists of ten into a notebook.

The first word I pulled was DRIPPING.

—

In my notes, I granted myself permission.

Go ahead with these words, let them inspire.

See what comes.

WORD LIST #1

DRIPPING

YOUNGER

LATTICE

GREAT

LIGHTLY

BEE

PURPLE

COME

SWEAR

HAIR

preface

FIT INTO ME

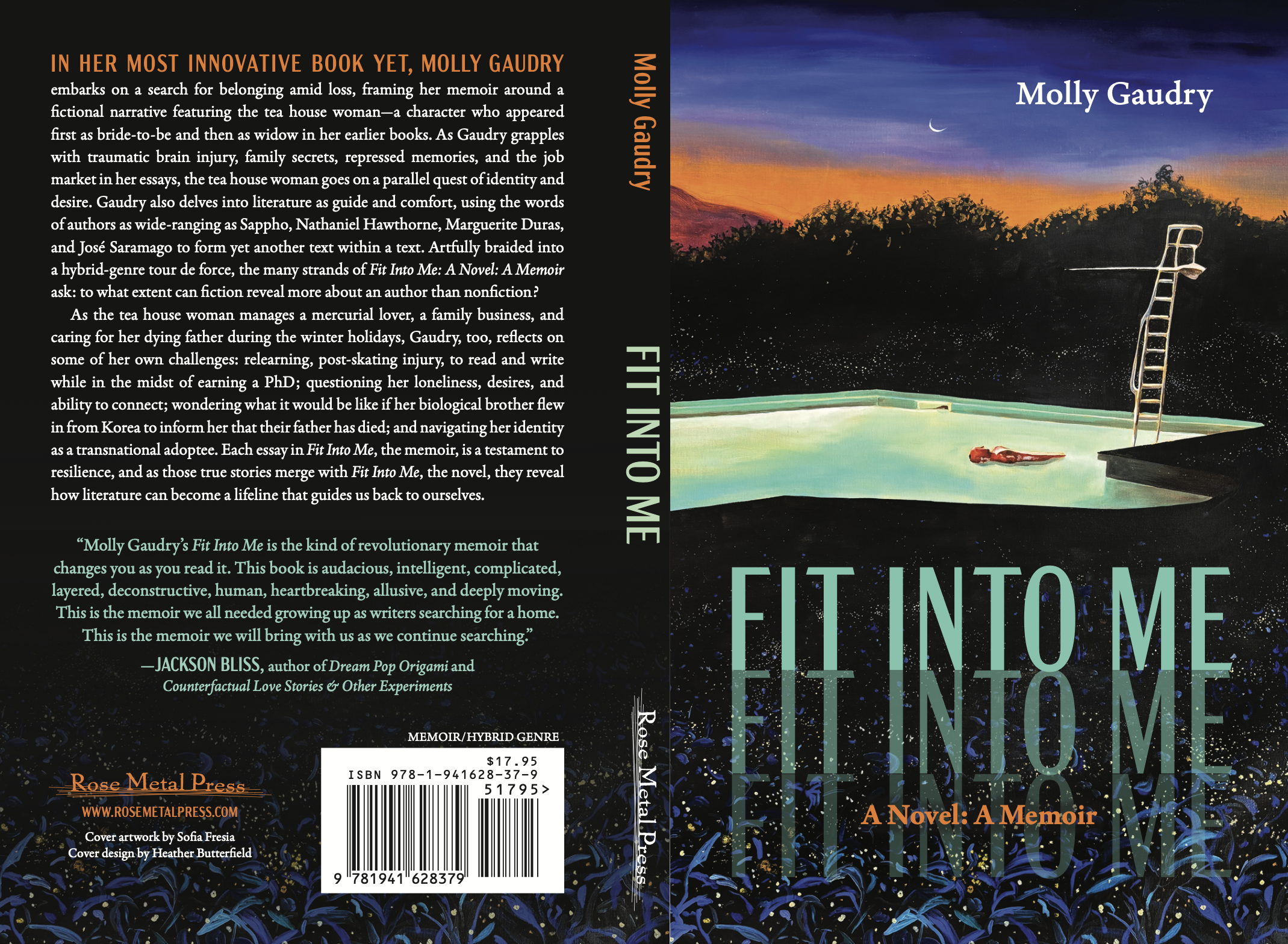

I write this novel in offering to the tea house woman, that complicated figure who appears first as bride-to-be in We Take Me Apart and then, years later, as widow in Desire: A Haunting, which I have only just completed.

This is a bad period for me. It’s the end of a book, and there’s a kind of loneliness, as if that closed book were going on still somewhere else, inside me.[3]

Like an open eye.[4]

Salt Lake City, Utah

February 2014

And so the first word of the tea house woman’s story is DRIPPING, which could refer to anything: the faulty kitchen faucet; the basement ceiling of the tea house after the flood; stems of wildflower bouquets pulled putrid from tall white pitchers; her own wet cunt.

In fact, dripping refers back to Sappho. The word appears twice in her body of work—first in Fragment 37:

in my dripping (pain)

And again in Fragment 119:

cloth dripping

Regarding Fragment 37, Anne Carson tells us the text is cited as Sappho’s in the following discussion of words for pain: And the Aeolic writers call pain a dripping… [as if a pain wounds] because it drips and flows.[5]

—

Translated differently by Mary Barnard, the fragment appears as follows:

Pain penetrates

me drop

by drop[6]

In her thesis, The Mary Barnard Translation of Sappho, Angela Christy speculates that Sappho was thinking of dripping stalagtites.

Barnard corrects her. I’m sure that she did not have stalagtites in mind, she writes, nor did I. I thought of a faucet dripping—in the next room, say—then of a heartbeat, then of the pulse, then of throbbing pain. The comparison is not with a hard stone pointed object, but with rhythmic liquid movement, inside the body.[7]

The tea house woman surprises herself by taking a new lover.

He is YOUNGER than her Portuguese lover, and this morning she lies

awake in bed waiting for him to stir. The rising sun through the trellis

beyond her bedroom window forms a LATTICE shadow over

her torso. She lifts

her hand into the light,

watches the pattern of the lines

moving over her skin.

The motion of her wrist

is reminiscent of Catherine the GREAT’s

upon receiving Marie Antoinette’s court

painter, Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun,

who later wrote, The sight of this famous woman

so impressed me that I found it impossible to think of anything:

I could only stare at her.[8]

The tea house woman slides down along

the body of her lover, takes his cock into her

mouth and sucks, LIGHTLY, lips soft as a BEE landing

on a plum blossom.

He is PURPLE. Hard.

Awake, he reaches with both arms,

pulls her toward him,

onto him. They are—no, we are—

chest to chest, and I am in your ear

now whispering, You’re going to make me COME.

This is new.

The tea house woman’s

husband had always finished first, even on

their wedding night, and he apologized the way men do

when they come too soon, and she hugged him and felt

almost like herself, comforting him, until it got to the point

where, listening to him snore, she would roll over and SWEAR

at the ceiling, trying to convince herself that next time would be better.[9]

Inevitably, during those early hours and before

the kitchen staff arrived, she found herself downstairs

with Nell, letting the older woman console her

over a pot of coffee and a plate of hot cinnamon

rolls. Imagine the kitchen

of a spreading old house in a country town.

A great black stove is its main feature;

but there is also a big round table

and a fireplace with two rocking chairs

placed in front of it.[10] Well,

Nell would say, retrieving the previous night’s chocolate trees

from the walk-in and placing them on the tops of freshly frosted,

coconut-dusted cupcakes, have you experimented with this?

Or, while cutting biscuits out of trifold dough, Maybe you could

wear that? Eventually—after her suggestion of open

and transparent communication backfired when her young friend,

after many weeks, finally mustered her courage to ask her husband

if there was anything she should be doing differently in bed and

he, in response, put a hand on her head and told her to stop overthinking it—

yes, finally even Nell threw her hands into the air, where they left

little puffs of flour, like clouds,

and said, Men, what can you do?[11]

Tell me what I can do for you, you say,

your hands clamped around

my hips and rocking them forward and back against yours,

my HAIR falling long down the sides of my face,

nearly onto your face, your eyes watching mine

for instructions, signs,

and I don’t know what I want or how to ask for it

until you stop, let go. Stunned, waiting, Don’t

stop, I say, and you flip me over, still

inside me, onto my back, Yes, like that,

as I push back against you, pulling

you closer, Yes, pushing back under your weight,

and forward, Yes,[12] until you fall heavy on top of me,

your eyes finally closing when we are—no, they are—

again chest to chest, and, as her young lover

rests his left temple in the cradle of her right shoulder

and jaw, the tea house woman stares up at the ceiling,

caressing his neck and back, thinking

it’s only fair for a woman to come more,

think of all the times they didn’t care.[13]

During this time, during these first early pages of Fit, I started blogging again.

Journaling out loud again. Reaching through the glow of the screen again. Inviting readers in again. Laying it all bare again. Splaying myself wide open again. Asking all the night owls and insomniacs to keep me company because I had always been and would always be one of them and I couldn’t sleep again.

Because I was writing again.

—

Because I love writing, and I’m miserable without it.[14]

Because I had to remember having suffered. The suffering was still there, but it was more even. The same with the emotion […]. But here, no; I can’t see or hear anything. I’ve merged into the characters.[15]

Because to tell her own story, a writer must make herself a character. To tell another person’s, a writer must make that person some version of herself, must find a way to inhabit her.[16]

—

Because when the fit of writing came on, she gave herself up to it with entire abandon, and led a blissful life, unconscious of want, care, or bad weather, while she sat safe and happy in her imaginary world, full of friends almost as real and dear to her as any in the flesh.[17]

Because then, of course, I got stuck. I didn’t know where to go from there, so I did what so many of us did back then: I blogged about not knowing where to go from there. Day by day, it felt like progress. To at least be writing about the writing—ruminating, investigating, doubting. And in my private journal, too, which I turned to every night and every morning, I wrote about the blogging, marking on paper anything potentially productive when it emerged on screen.

Because writing is a geologically slow process, the drip-drip of a stalactite forming.[18]

NOTES

[1] Frances Hodgson Burnett, “Melchisedec,” A Little Princess (New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2012), 117.

[2] Arundhati Roy, “The Cost of Living,” The God of Small Things (New York: Random House, 2008), 317.

[3] Marguerite Duras, “Alan Veinstein,” Practicalities, translated by Barbara Bray (New York: Grove Press, 1990), 69.

[4] Margaret Atwood, “You Fit Into Me,” Tools of the Writer’s Craft by Sands Hall (San Francisco: Moving Finger Press, 2011), 42.

[5] Sappho, If Not, Winter, translated by Anne Carson (New York: Vintage Books, 2003), 365.

[6] Mary Barnard, Sappho: A New Translation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965), 61.

[7] Mary Barnard, quoted in Bill Donahue, “Channeling Sappho, Reed Magazine (Autumn 2009), 5.

[8] Louise Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, quoted in Lydia Figes’s “Catherine the Great: Sex, Slander, and Absolute Power,” Art UK, October 04, 2019.

[9] Amy Bloom, “Sleepwalking,” Come to Me (New York: HarperPerennial, 1993), 47.

[10] Truman Capote, “A Christmas Memory,” A Christmas Memory (New York: The Modern Library, 2007), 3.

[11] Weike Wang, “Omakase,” The O. Henry Prize Stories 2019, edited by Laura Furman (New York: Anchor Books, 2019), 274.

[12] James Joyce, “Penelope,” Ulysses (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), 644.

[13] Bernadette Mayer, “‘First Turn to Me…,’” A Bernadette Mayer Reader (New York: New Directions Books, 1992), 123.

[14] Kathryn Harrison, “Please Stop Thinking,” Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration, and the Artistic Process, ed. Joe Fassler (New York: Penguin Books, 2017), 111.

[15] Marguerite Duras, “The Book,” Practicalities, 79.

[16] Jenn Shapland, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (Portland: Tin House Books, 2020), 3–4.

[17] Louisa May Alcott, Little Women (New York: Puffin Books, 2014), 418.

[18] Maggie Shipstead, “Time Passes,” Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration, and the Artistic Process, ed. Joe Fassler (New York: Penguin Books, 2017), 201.